A calorie is a calorie ... Not!

There are a lot of myths and dogmas perpetrated throughout health, nutrition and diet. The reasons are legion: inappropriate research, misinterpretation of research, commercial spin for business and financial objectives, politics, personal ego, and outright deception, to name but a few.

The myth that “a calorie is a calorie” is one of the most pervasive, long lasting, and pernicious. This myth, for example, has enabled the sugar manufacturers to aver for decades that sugar is a vital and necessary ingredient in the human diet, The Sugar Association, “the scientific voice of the sugar industry,” (https://www.sugar.org/about/). Here’s its position: “The cause of obesity is a complex issue, and there are many contributing factors. These factors include excessive caloric intake, genetics and low physical activity levels. Just like protein, starch, fat, alcohol and other carbohydrates, sugar is a source of calories in the diet. Excessive calories from any source, including sugar, can lead to weight gain, increasing the risk of obesity and other chronic diseases. A systematic review of the evidence concluded that “if there are any adverse effects of sugar, they are due entirely to the calories it provides.” Additionally, three authoritative scientific organizations — the U.S. Institute of Medicine, European Food Safety Authority and U.K. Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition— each conducted extensive scientific reviews of added sugars and obesity and found no unique role for added sugars in the development of obesity. … the scientific evidence consistently shows that a healthy lifestyle based on moderation, a variety of food choices and physical activity tends to lead to the best outcomes when compared with simply focusing on cutting out or adding one ingredient or another. As long as people are conscious of their caloric intake, they can enjoy sugar in moderation.” https://www.sugar.org/health/body-weight/ In other words, “a calorie is a calorie.”

Aside … an issue almost universally raised in research about health issues is the validity of scientific research upon which analyses and policy recommendations are based. In one sense it comes down to asking about and understanding who funded the reported research. The reported research underlying the above quote from The Sugar Association was all funded by sugar organizations or sugar producers. You decide.

Everybody talks about calories, but what are they? A “calorie” is the amount of heat required at a pressure of one atmosphere to raise the temperature of one gram of water one degree Celsius, about 4.184 joules. This “calorie” is called the “small calorie.” A “big calorie” is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of water one degree Celsius, one thousand times larger than a small calorie. A big calorie is 3.968 Btu. Time to haul out the old chemistry or physics book? (For the non-metricized, a British thermal unit is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit.) In terms of diet, a “calorie” is one “large calorie,” the heat-producing or energy-producing effect of food when oxidized in the body. Merriam-Webster (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/calorie). You will often see the expression “kcal” to describe dietary calories.

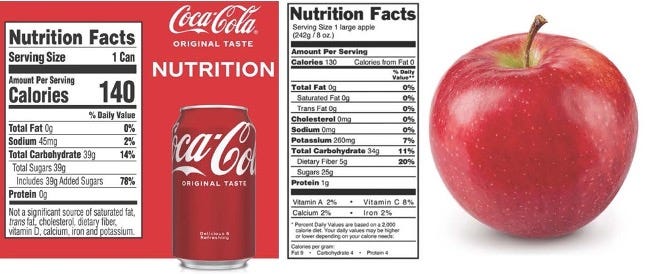

The fundamental claim of “a calorie is a calorie” is that it makes no difference whether you get a 140 hundred calories from a can of Coca-Cola or a large apple, the effect on the human body is the same. Sorry, not true. You don’t just eat “calories,” they are delivered with different macronutrients that determine and regulate body functions. The primary ingredient in Coca-Cola is 39 grams of added sugar, high fructose corn syrup (HFCS); no added sugar in the apple plus vitamins and minerals. Furthermore, different foods are processed differently in the body.

There are two main types of sugars in our diet, glucose and fructose. Gram for gram they provide the same number of calories, energy, but they are metabolized completely differently in the body. Glucose is metabolized in every cell of your body. It is the source of your energy, and is the most efficient form of energy transfer. Lustig, R., “Fructose: Metabolic, Hedonic, and Societal Parallels with Ethanol,” J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 110(9) 1307-1321 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.06.008 Fructose, on the other hand, can only be metabolized by the liver. Bray, G., “How bad is fructose?” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86(4):895-6 (Oct. 2007). https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/86.4.895 The really bad news is the liver uses fructose to create fat. Overloading the liver with fructose can lead to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, fat accumulating in the cells of the liver. Your liver on too much fructose looks just like the liver of someone who drinks too much alcohol. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) now affects up to 30 percent of US adults, and from 70 to 90 percent of people who are obese or have diabetes. Heart Health, Harvard Health Publishing (September 1, 2011). https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/abundance-of-fructose-not-good-for-the-liver-heart

Additionally, too much fructose can lead to insulin resistance, the main feature of metabolic syndrome, abdominal fat gain, inflammation, increased triglyceride concentrations in the blood and liver, oxidative stress, increased blood pressure, and elevated uric acid levels. Muriel, P, López-Sánchez, P, and Ramos-Tovar, E., “Fructose and the Liver,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(13) 6969 (June 28, 202). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22136969

Fructose is naturally found in fruits, however, here it is bound to fiber that slows its absorption. More importantly, fruits and vegetables contain many other essential nutrients that modulate the effects of the fructose in the body.

Most damaging to dieters is fructose does not stimulate the satiety centers in the brain. In other words, it does not trigger that “I’m full” feeling when you eat so you want to keep eating. Page, K. et al., “Effects of fructose vs glucose on regional cerebral blood flow in brain regions involved with appetite and reward pathways,” JAMA. 309(1):63-70 (January 2, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.116975 Erratum in: JAMA. 309(17):1773 (May 1, 2013.)

The single largest source of fructose in our diet is processed food made with high fructose corn syrup (HFCS); the single largest food using HFCS is soft drinks … soda, fruit juices, etc. Clearly, with respect to sweeteners, a calorie is not just a calorie. However, the American Beverage Association has long cited the myth to deflect criticism of soft drinks. “… [W]hen it comes to obesity, a calorie is a calorie regardless of the source. Simply put, if you take in more calories from the foods and beverages you consume than those you burn off through physical activity, then you’ll gain weight. It doesn’t matter if those calories come from apples, cookies, hamburgers, soft drinks or anything else.” American Beverage (February 21, 2012). https://www.americanbeverage.org/education-resources/blog/post/a-calorie-is-a-calorie/ The myth lives on.

A second reason a calorie is not just a calorie has to do with how much energy the body has to expend to metabolize food. Protein requires more energy to metabolize than do fat or carbohydrates. Thus, protein calories are less fattening than calories from fat or carbohydrate. Whole foods take more energy to digest than processed foods. Feinman, R. and Fine, E., “’A calorie is a calorie’ violates the second law of thermodynamics,” Nutr. J. 3:9 (July 28, 2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-3-9; Buchholz , C. and Schoeller, D. “Is a calorie a calorie?” Am. J. Clin. Nutr.79(5):899S–906S (May 2004). https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.5.899S; Johnston, C., Day, C., and Swan, P., “Postprandial thermogenesis is increased 100% on a high-protein, low-fat diet versus a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in healthy, young women,” J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 21(1):55-61 (February 2002). https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2002.10719194.

The story about protein gets even better. Protein tends to significantly reduce appetite. Increasing your protein intake leads to eating fewer calories overall. Skov, A. et al., “Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity,” Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 23(5):528-36 (May 1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0800867 Furthermore, one reason why low carbohydrate diets lead to more weight loss than low fat diets is low carbohydrate diets tend to include more protein, which leads to satiety. Veldhorst, M., Westerterp-Plantenga, M., and Westerterp, K., “Gluconeogenesis and energy expenditure after a high-protein, carbohydrate-free diet,” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 90(3):519-26 (September 2009). https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.27834

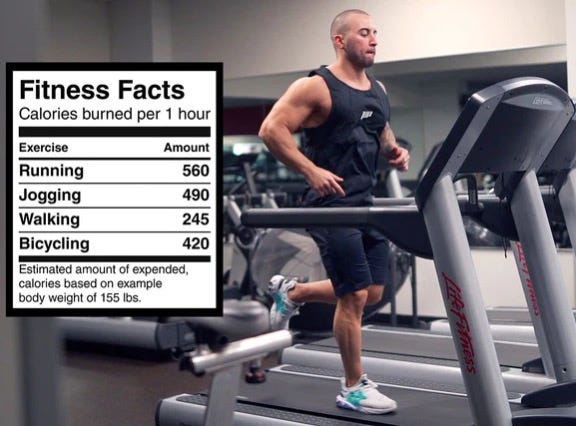

Physiologically it is clear a calorie is not just a calorie despite the loud and continuous trumpeting by commercially vested interests. Unfortunately, the persistence of the myth also leads to often severe social issues, that is, person-shaming and body-shaming, sometimes also called fat-shaming. The premise of the American Beverage Association quote above is that weight control is simply a matter of caloric input and output, calories consumed verses calories expended. Want to lose weight … eat less and exercise more … and it is ok to consume a Big Gulp after exercising if you exercise long enough and hard enough. How many of you know someone that exercises regularly, counts calories, and still cannot lose weight? The reality is there is no way anyone could actually burn off the calories supplied by our current food supply system. Your caloric output is controlled by your body and is dependent upon both the quantity and the quality of the food you eat. Newgard, C., et al., “A Branched-Chain Amino Acid-Related Metabolic Signature That Differentiates Obese and Lean Humans and Contributes to Insulin Resistance,” Cell Metab. 9:311-26 (2009); Gibbons, A., “The Calorie Counter,” Science 375:6582 (February 17, 2022); Pontzer, H., “New Human Metabolism Research Upends Conventional Wisdom about How We Burn Calories,” Scientific American (January 1, 2023).

The purveyors of the “a calorie is a calorie” myth also assert that “we’re eating to damn much.” The Conversation, “Is it our fault if we eat too many calories?” (August 9, 2016) https://theconversation.com/is-it-our-fault-if-we-eat-too-many-calories-63730 The implication of this assertion is we are eating more of everything, but we are not. We are eating more of some foods and less of others. We have been eating many more processed foods and fewer natural foods (a trend that seems to be reversing among some segments of the population); mainly foods and drinks that have a high sugar, fat, or alcohol content, or a combination of all three, but little or no other nutritional value, “empty calories.”

One of the major results of the pervasiveness of the “a calorie is a calorie” myth has been the explosive rise in the use of artificial sweeteners … “we want the sweetness, not the calories.”

We are genetically programmed for sweetness. Anthropologically, our ancestors faced continuing challenges of securing enough to eat to survive. The foundational requirement was sufficient calories to provide the energy necessary to live. Foraging was dominant. Identifying sweet food sources increased the probability of survival; sweetness is an indication of available calories. Quickly identifying sweet plants increased the efficiency of the food search; our ancestors were able focus on what was known to be sweet and not spend time collecting and processing other potential foods. Evolution has carried the attraction of sweetness to modern man. Wooding, S., “A taste for sweet – an anthropologist explains the evolutionary origins of why you’re programmed to love sugar,” The Conversation (January 6, 2022). https://theconversation.com/a-taste-for-sweet-an-anthropologist-explains-the-evolutionary-origins-of-why-youre-programmed-to-love-sugar-173197

Taste starts in the mouth. The surface of your tongue is covered with receptors that respond to different tastes. A molecule of sugar triggers your taste receptor for sweetness. Artificial sweetener molecules trigger the same sweetness receptors. However, your body does not process artificial sweeteners the same way as sugars; your body cannot break them down into calories. You get the sweet taste you want without calories.

The first commercially viable artificial sweetener, saccharin was accidentally discovered in 1878 at Johns Hopkins University. Today you have a plethora of choices (here listed in chemical alphabetical order): aspartame, 200 times sweeter than sugar … NutraSweet, Equal or Sugar Twin; acesulfame potassium, also known as acesulfame K, 200 times sweeter than sugar, used primarily for baking and cooking … Sunnet or Sweet One; advantame, 20,000 times sweeter than sugar, used for cooking and baking; aspartame-acesulfame salt, 350 times sweeter than suger … Twinsweet; cyclamate, 50 times sweeter than sugar, banned in the US since 1970; neotame, 13,000 times sweeter than sugar … Newtame; neohesperidin, 340 times sweeter than sugar, suited for baking, cooking and mixing with acidic foods, not approved in the US; saccharin, 700 times sweeter than sugar … Sweet’N Low, Sweet Twin or Necta Sweet; stevia, 200 times sweeter than sugar, derived from a plant … Stevia, Truvia, PureVia, others; sucralose, 600 times sweeter than sugar, suited for baking, cooking and mixing with acidic foods … Splenda. Basson, A., Rodriguez-Palacios, A., and Cominelli, F., “Artificial Sweeteners: History and New Concepts on Inflammation,” Front. Nutr. 8:746247 (September 24, 2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.746247; Petre, A., “Artificial Sweeteners: Good or Bad?” Healthline (August 19, 2020). https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/artificial-sweeteners-good-or-bad; Hicks, J., “The Pursuit of Sweet,” Science History Institute (May 2, 2010). https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/the-pursuit-of-sweet

Unfortunately, not all is wonderful with artificial sweeteners. Artificial sweeteners lead to a false promise, you can eat more without gaining weight. They can negatively affect gut bacteria and your brain, and can lead to a variety of more serious medical issues. Tey, S., et al., “Effects of aspartame-, monk fruit-, stevia- and sucrose-sweetened beverages on postprandial glucose, insulin and energy intake,” Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 41(3):450-457 (March 2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.225; Azad, M., et al., “Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies,” CMAJ. 189(28):E929-E939 (July 17, m2017). https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.161390

The World Health Organization (WHO) advises not to use non-sugar sweeteners for weight control. The recommendation is based on the findings of a systematic review of the available evidence which suggests that use of non-sugar sweeteners (NSS) does not confer any long-term benefit in reducing body fat in adults or children. Results of the review also suggest that there may be potential undesirable effects from long-term use of NSS, such as an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and mortality in adults. Francesco Branca, WHO Director for Nutrition and Food Safety, stated, “NSS are not essential dietary factors and have no nutritional value. People should reduce the sweetness of the diet altogether, starting early in life, to improve their health.” WHO (May 15, 2023). https://www.who.int/news/item/15-05-2023-who-advises-not-to-use-non-sugar-sweeteners-for-weight-control-in-newly-released-guideline

“[P]erhaps the dogma should be restated thus: a calorie burned is a calorie burned, but a calorie eaten is not a calorie eaten. And therein lies the key to understanding the obesity pandemic. The quality of what we eat determines the quantity.” (Emphasis added.) Lustig, R., The Hacking of The American Mind: The Science Behind the Corporate Takeover of Our Bodies and Brains (Avery Press, Sept. 12, 2017).

A calorie is NOT just a calorie. Choose wisely; avoid Frankenfoods, eat natural whole foods, avoid artificial sweeteners.