Do you suffer from a food addiction?

What are you talking about? How can food be addictive? “I like French fries and potato chips … and donuts … but, I’m not addicted to them. I can take them or leave them.” Quizzingly, why in reaction to the question did you immediately mention French fries, chips and donuts? Is there something inherent in these foods that you recognize as triggering your response?

To quote Hollywood Montrose:

… “It's those jelly doughnuts. They call to me in the middle of the night: ‘Hollywood! Hollywood! Come and get me, Hollywood!’ I can't stay away from them.” … (Mannequin, 1987)

You may have encountered some of the recent media about food addiction. A CNN story entitled “Why a food addiction many Americans say they struggle with is one experts can’t agree on,” on June 15, 2023, articulated a fundamental question, “is food addiction a real thing?” https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/15/health/food-addiction-help-symptoms-wellness/index.html On October 23, 2023, USA Today reported a “Study: Foods like ice cream, chips and candy are just as addictive as cigarettes or heroin.” https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/10/23/study-ice-cream-chips-addictive-cigarettes-heroin-drugs/71286591007/ A few days later MSN broadcast an interview “Wynonna Judd Talks About Overcoming Food Addiction and Health Scare.” https://www.msn.com/en-us/music/celebrity/wynonna-judd-talks-overcoming-food-addiction-and-health-scare/ar-AA1j6yxe Apple has a continuing podcast “Food Addiction, the Problem and the Solution.”

Let’s start at the beginning. There has been a continuing debate about whether food addiction is real; the concept remains controversial in the scientific community. First, there is no accepted definition of food addiction. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) does not include a standalone category for diagnosing food addiction. However, researchers have identified some behaviors associated with a concept of food addiction by analogizing to established addictive behavioral research, such as cravings for illicit drugs. Gordon, E., et al., “What Is the Evidence for "Food Addiction?" A Systematic Review,” Nutrients 10(4):477 (Apr. 12, 2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040477

Can we default to common language or other sources for a definition? The Oxford English Dictionary, the American Psychological Association, the American Society of Addiction Medicine, and the American Psychiatric Association have all defined addiction. Therein lies a second issue, all of these posited definitions are based upon identification of an addictive substance such as nicotine or caffeine. Is there a nutrient or combination of nutrients in food that cause food addiction?

Researchers have identified some behaviors they associate with a concept of food addiction, such as compulsive overeating, even in the absence of hunger; cravings for particular kinds of foods, particularly high-fat and sugary foods; binge eating; disoriented eating patterns; difficulty in controlling food intake; and bulimia nervosa; for example. Lerma-Cabrera, J., et al., “Food addiction as a new piece of the obesity framework,” Nutr. J. 15(5) (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0124-6; Lennerz, B., and J. Lennerz, “Food Addiction, High-Glycemic-Index Carbohydrates, and Obesity,” Clin. Chem. 64(1):64-71 (Jan. 2018). https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2017.273532; Novelle, M. and C. Diéguez, “Food Addiction and Binge Eating: Lessons Learned from Animal Models,” Nutrients 10(1):71(Jan. 11, 2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010071; Hilker, I., et al., “Food Addiction in Bulimia Nervosa: Clinical Correlates and Association with Response to a Brief Psychoeducational Intervention,” Eur. Eat Disord. Rev. 24(6):482-488 (Nov. 2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2473

It has been found that the brain mechanisms of people demonstrating behaviors associated with food addiction are similar to people with substance dependence, such as drug addicts. On this basis the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) was developed in 2009 to provide a standardized self-report instrument for the assessment of food addiction. Gearhardt, A., et al., “Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS),” APA PsycTests (2009).

https://doi.org/10.1037/t03319-000; Meule, A. and A. Gearhardt, “Five years of the Yale Food Addiction Scale: Taking stock and moving forward,” Current Addiction Reports 1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-014-0021-z The YFAS includes twenty-five questions that explore behaviors that are similar to symptoms for substance dependence as enumerated in the earlier DSM-IV. It has several response formats such as frequency scales, yes or no questions, and free form responses. Gearhardt, A., et al., “Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale,” Appetite 52(2):430-6 (Apr. 2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003

Here's a sample. Question 2 is, “I find myself continuing to consume certain foods even though I am no longer hungry.” The response scores are: “Never” = 0, “Once a Month” =1, “2-4 Times a Month” = 2, “2-3 Times a Week” = 3, and “4 or More Times a Week, or Daily” = 4.

Question 18 is, “My food consumption has caused significant physical problems or made a physical problem worse.” “No” = 0; “Yes” = 1.

Question 25 is, “I find that when I start eating certain foods, I end up eating much more than planned.” The response scores are: “1 or Fewer Times,” “2 Times,” “3 Times,” “4 Times,” and “5 or More Times.”

The behaviors the YFAS explores are:

1. Taking in more of a substance, and for longer, than intended or preferred (Questions #1, #2, #3)

2. A persistent desire or repeated unsuccessful attempts to quit the unwanted substance or behavior (Questions #4, #22, # 24, #25)

3. Spending a lot of time or effort to obtain, use, and/or recover from the substance or behavior (Questions #5, #6, #7)

4. The person has given up or reduced important social, occupational, or recreational activities because of the substance or behavior (Questions #8, #9, #10, #11)

5. The person keeps consuming the substance or doing the behavior, despite knowing about adverse consequences, e.g. feeling ill (Question #19)

6. It takes more and more of the substance or behavior to soothe the person or create the desired effects, and often the substance or behavior doesn’t quite “do the job” any more (Questions #20, #21)

7. Characteristic withdrawal symptoms; somehow the person attempts to relieve withdrawal (Questions #12, #13, #14)

8. The substance or behavior causes clinically significant impairment or distress (Questions #15, #16)

“[The YFAS] includes two scoring options: 1) a “symptom count” ranging from 0 to 7 that reflects the number of addiction-like criteria endorsed, and 2) a dichotomous “diagnosis” that indicates whether a threshold of three or more “symptoms” plus clinically significant impairment or distress has been met.” In other words, the higher the total number score, the more you display addictive behaviors. Is there a threshold? “Yale Food Addiction Scale,” Food and Addiction Science & Treatment Lab, University of Michigan. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/fastlab/yale-food-addiction-scale/

YFAS 2.0 was released in 2016 to reflect the significant changes to the substance-related and addictive disorders sections of DSM-5. Perhaps the most significant change in YFAS 2.0 is the food addiction threshold is more strongly associated with obesity than in the original YFAS. In a simplified sense, you are considered addicted to food at a lower total score. Gearhardt, A., et al., “Development of the Yale Food Addiction Scale Version 2.0,” Psychol. Addict Behav. 30(1):113-21 (Feb. 2016). https//doi.org/10.1037/adb0000136

Where are we today? Research shows that daily snacking on processed foods, the kinds you find in the center aisles of the grocery store, rewires the brain’s reward circuits just like cocaine and nicotine do. However, there is no single opiatelike substance that can be identified that leads to food addiction. So what in food lights up the brain? Research suggests that if carbohydrates (sugar is the real bad guy here) are mixed together with fats in unnaturally large doses, they create an express lane to the brain’s reward system similar to cocaine and nicotine. Interestingly, equally caloric foods that contain only a carbohydrate or only a fat do not have the same effect. “Ultraprocessed foods are hijacking the brain in a way you’d see with addiction to drugs,” says Nicole Avena, a neuroscientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, NY. Thanarajah, E., et al., “Habitual daily intake of a sweet and fatty snack modulates reward processing in humans,” Cell Metabolism 35:571-584 (Apr. 4, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.02.015; Kenny, P., “The Food Addiction,” SA Special Editions 24(2s):46-51 (Jun. 2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamericanfood0615-46; Agnes, A., et al., “Ultra-processed foods and binge eating: A retrospective observational study,” Nutrition 84:111023 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2020.111023; DiFeliceantonio, A., et al., “Supra-Additive Effects of Combining Fat and Carbohydrate on Food Reward,” Cell Metabol.28(1):33-44 (Jul.3, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.018; Vasiliu, O., “Current Status of Evidence for a New Diagnosis: Food Addiction - A Literature Review,” Front. Psychiatry 12:824936 (Jan. 10, 2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.824936

The Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at the University of Michigan undertook a poll to assess possible food addiction in older adults. The results of the poll released on January 30, 2023, showed “… about 13% of people aged 50 to 80 showed signs of addiction ….” The poll used “a set of 13 questions to measure whether, and how often, older adults experienced the core indicators of addiction in their relationship with highly processed foods such as sweets, salty snacks, sugary drinks and fast food. … to meet the criteria for an addiction to highly processed food on the scale used in the poll, older adults had to report experiencing at least two of 11 symptoms of addiction in their intake of highly processed food, as well as report significant eating-related distress or life problems multiple times a week. These are the same criteria used to diagnose addiction-related problems with alcohol, tobacco and other addictive substances. … By these criteria, addiction to highly processed foods was seen in: 17% of adults aged 50 to 64 and 8% of adults aged 65 to 80; 22% of women aged 50 to 64 and 18% of women aged 50 to 80. … The most commonly reported symptom of an addiction to highly processed foods in older adults was intense cravings. Almost 1 in 4 (24%) said that at least once a week they had such a strong urge to eat highly processed food that they couldn’t think of anything else. And 19% said that at least 2 to 3 times a week they had tried and failed to cut down on, or stop eating, these kinds of foods. … Twelve percent said that their eating behavior caused them a lot of distress 2 to 3 times a week or more.” Gearhardt, A., et al., “Addiction to Highly Processed Food Among Older Adults,” University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging. (Jan/Feb 2023). https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/6792

A more recent study reported that ultra-processed food addiction is estimated to occur in fourteen percent (14%) of adults and twelve percent (12%) of children. For comparison, levels of addiction in other legal substances in adults are fourteen percent (14%) for alcohol and eighteen percent (18%) for tobacco. The level of 12 percent for children is “unprecedented,” the researchers noted. Gearhardt, A., et al., “Social, clinical, and policy implications of ultra-processed food addiction,” BMJ 2023:383 (Oct. 9, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075354; Praxedes, D., et al., “Prevalence of food addiction determined by the Yale Food Addiction Scale and associated factors: A systematic review with meta-analysis,” European Eating Disorders Rev. 30(2):85-95 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2878

The research is focused on ultra-processed foods. Is there a difference between unprocessed, processed and ultra-processed foods? By definition, a processed food is simply one that has been altered from its original form. The International Food Information Council defines processing as “any deliberate change in a food that occurs before it is ready for us to eat. Heating, pasteurizing, canning, and drying are all considered forms of processing, for example. https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/IFIC_Handout_processed_foods.pdf

The idea of ultra-processed foods was introduced in 2009 by a Brazilian nutrition researcher, Carlos A. Monteiro, a Professor of Nutrition and Public Health at the School of Public Health, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, where he chairs the Center for Epidemiological Studies in Health and Nutrition.

In 2010 Monteiro and his colleagues created a classification system for processed foods that is today called NOVA. At one end of the NOVA spectrum are unprocessed or minimally processed foods such as vegetables, fresh fruits, and eggs, for example. At the other end are ultra-processed foods, defined as “industrial formulations with five or more ingredients.” Ultra-processed foods often include ingredients used in processed foods, for example, sugar, salt, oils, fats, stabilizers, and preservatives. However, there are substances only found in ultra-processed food products such as “casein, lactose, whey, and gluten, and some derived from further processing of food constituents, such as hydrogenated or interesterified oils, hydrolyzed proteins, soy protein isolate, maltodextrin, invert sugar and high fructose corn syrup. Classes of additive only found in ultra-processed products include dyes and other colours, colour stabilizers, flavours, flavour enhancers, non-sugar sweeteners, and processing aids such as carbonating, firming, bulking and anti-bulking, de-foaming, anti-caking and glazing agents, emulsifiers, sequestrants and humectants.” Monteiro, C., “Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing,” Public Health Nutrition 12(5):729-731 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980009005291; Monteiro, C., et al., “A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing,” Cad Saude Publica 26(11):2039-49 (Nov. 2010). https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2010001100005; Monteiro, C., et al., “The Food System,” World Nutrition 7(1-3) (Jan-Mar 2016). …” https://archive.wphna.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/WN-2016-7-1-3-28-38-Monteiro-Cannon-Levy-et-al-NOVA.pdf This list is illustrative, not exhaustive; in today’s food environment it goes on and on with new additives introduced almost daily without any assessment of their health implications. In other words, read food labels. If there are more than five ingredients, question whether you want to eat it. If there are words you cannot pronounce or do not know what they mean, you should not eat it.

In 2002 researchers Ashley N. Gearhardt, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, and Alexandra G. DiFeliceantonio, Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC and Department of Human Nutrition Foods, and Exercise, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, both cited herein, published an opinion that ultra-processed foods should be classified as addictive on the same basis that tobacco was classified as addictive. Gearhardt, A., and A. DiFeliceantonio, “Highly processed foods can be considered addictive substances based on established scientific criteria,” Addiction 118(4):589-598 (Nov. 9, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16065 What do you think is the likelihood of this happening?

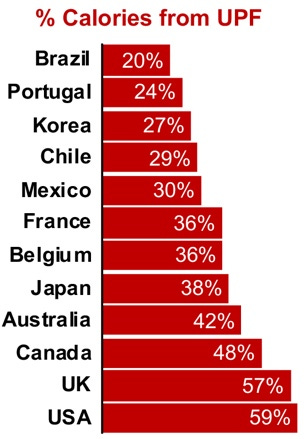

Processed foods, especially ultra-processed foods, continuously increased among adults in the U.S. from 2001 to 2018. Ultra-processed foods currently make up nearly sixty percent (60%) of what the typical adult eats, and nearly seventy percent (70%) of what kids eat. Ultra-processed foods comprise fifty-eight percent (58%) of the calories consumed in the U.S. Filippa, J., et al., “Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018, Am. J. Clin. Nutri.115(1):211-221 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab305; Godoy, M, “What we know about the health risks of ultra-processed foods,” NPR (May 25, 2023). https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/05/25/1178163270/ultra-processed-foods-health-risk-weight-gain; Steele, E., et al., “Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study,” BMJ Open 6(3):e009892 (2016). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009892

While the availability of ultra-processed foods (UPF) is most prevalent in the US, ultra-processed foods are becoming a worldwide problem. Monteiro, C., et al., “Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system,” Obesity Reviews 14(Suppl 2):21-28 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12107; Global Food Research Program, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, “Ultra-processed foods: A global threat to public health,” Fact Sheet (May 2021).

The industrial food companies know what they are doing. They are purposely adding salt, sugar and fats to foods to get us hooked. Kravitz, M., “Food Companies Are Making Their Products Addictive, and It’s Sickening (Literally),” Independent Media Institute (Mar. 26, 2019). https://www.ecowatch.com/food-companies-making-products-addictive-2632845184.html; Moss, M., Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us (Random House, 2014); Moss, M., Hooked: Food, Free Will, and How the Food Giants Exploit Our Addictions (Random House, 2021). “Bet you can’t eat just one.”

Your choice. What do you want to put in your body? I go back to Michael Pollan, “don’t eat anything your grandmother didn’t eat.”

YES to our being more educated abut processed food - thank you