Farm-to-Table

How many restaurants you visit advertise they are “farm-to-table”? What exactly does “farm-to-table” mean? What do you think the restaurant thinks it means? What do you think it means? Does “farm-to-table” apply to your own cooking and eating at home?

Go on yelp.com and search for “farm-to-table restaurants near me.” And the search results? Don’t like the results, try opentable.com. Any difference? What defines the restaurants that appear in the search results? Hint, they use the terms “farm-to-table” in the description of their restaurant that they provide to Yelp and Open Table.

There is no cut and dry definition of “farm-to-table.” Broadly, the “farm-to-table” movement refers to food made from locally-sourced ingredients, most often assumed to be “natural” or “organic.”

But what are “locally-sourced ingredients?” Is there a pre-defined distance that is considered “local”; a farm inside the arbitrary radius is local by definition, outside not? What about ingredients that are simply not available locally, for example, coffee beans? Coffee beans can only commercially be grown in Hawaii and southern California. They are also grown in Puerto Rico, a US territory. Is it sufficient that imported beans be roasted locally to be called “locally-sourced”?

Let’s step back from the definitional quagmire and look at the attitudes and philosophy behind the farm-to-table movement.

“One very important concept I teach students is that farm to table isn’t necessarily a style of cooking, but a spirit of cooking. It’s a philosophy in which chefs wish to prepare for their guests the most flavorful, tastiest, nutrient-rich food they can. This often means that sourcing is based on local ingredients,” says Larry Forgione, co-founder and culinary director of the Culinary Institute of America’s American Food Studies: Farm-to-Table Cooking curriculum. Forgione is often credited with leading the cultural charge toward farm-to-table. Forgione continues, “The CIA program studies the history, values, and future of farm-to-table cooking in America. I firmly believe this begins with understanding the importance of relationships with farmers.”

https://www.fsrmagazine.com/chef-profiles/farm-table-chef-embraces-spirit-cooking-not-style

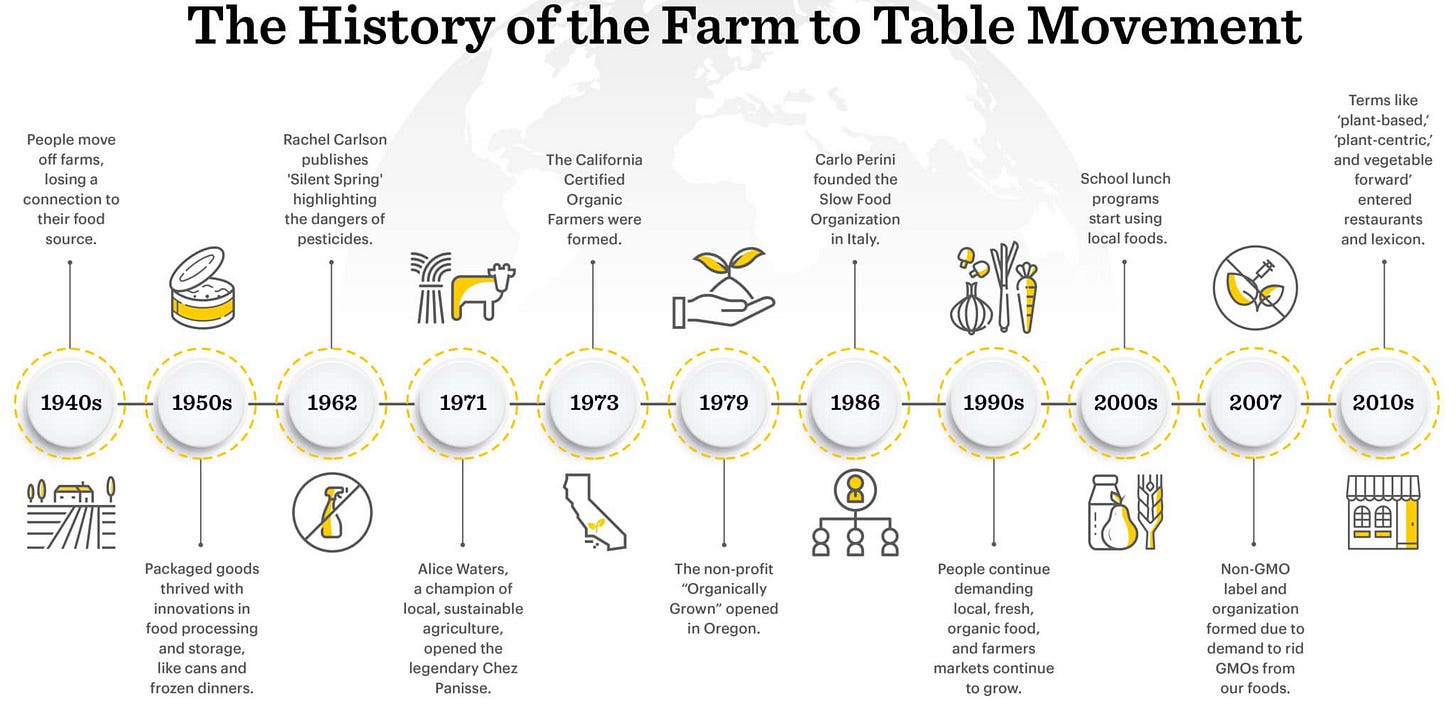

Whence cometh the farm-to-table movement? Taking a long view, in 1810 Nicolas Appert, known as the “Father of Food Science,” began experimenting with food preservation using heat, glass bottles, cork and wax. La Maison Appert (The House of Appert) in Massy, near Paris, became the first food-bottling factory in the world. In the 1860’s Louis Pasteur tremendously advanced long-term storage and transport of food. The work of these two men was foundational to the development of the tin can, which would become particularly popular with the start of World War I and the high demand for cheap, long-lasting, transportable food for soldiers.

World War II helped to speed up the development of ready-to-eat packaged meals. Also, during this time, the working middle class began to expand around the world, bringing increased demand for fast meals with a long shelf-life. If you are old enough, you might have had the opportunity to try the famous, or infamous, C-rations of WWII, Field Rations, Type C. If some ineffable spirit moves you, you may find some relic cans in Army-Navy Surplus stores, although I would not be tempted to try to eat from them. The more modern version, Meal, Ready-to-Eat, MRE, is commonly available.

Pre-packaged processed foods peaked in the 1950s. Consumers were bombarded with pre-packaged meals, remember the early television ads for Swanson TV Dinners? Convenience, not nutrition or flavor. They are still available in your grocery store today and, hopefully, with better nutrition and flavor (still industrial agriculture).

Slowly in the 1960s and 1970s food choices began to change. The hippy counterculture was a major influence with itsfundamental ethos of harmony with nature, communal living, and artistic experimentation, including food.

A seminal event in the farm-to-table movement occurred in 1971 when Alice Waters opened the restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkely, California. Waters’ vision for Chez Panisse was a place where she could cook for friends the way she saw cooking in rural France where cafés changed their menus daily based on what was available locally in that season. Many successful and prominent chefs opened restaurants embodying farm-to-table based on their experiences at Chez Panisse.

https://upserve.com/restaurant-insider/history-farm-table-movement/

While Waters’ Chez Panisse opening is considered pivotal in the modern farm-to-table movement, there was a much earlier version of farm-to-table established by the US Government during the administration of President Woodrow Wilson.

“[The] farm-to-table movement was an ambitious postal initiative that took place during President Woodrow Wilson's administration, seeking to transport produce directly from rural areas to cities. The program entailed picking up farm-fresh products - butter, eggs, poultry, vegetables, to name a few - and taking them as directly and quickly as possible to urban destinations. It was conceived and launched in peacetime, but took on additional significance during America's eighteen-month involvement during what we know today as World War I. In the course of that bloody conflict, the experimental motor truck routes set up as part of that program were seen by many as important to the nation-wide food conservation campaign.”

Cullen, R.G. (2010). "Food will win the war": Motor trucks and the Farm-To-Table postal delivery program, 1917-1918. In Lera, T. (Ed.), The Winton M. Blount Postal History Symposia: Select Papers, 2006-2009. Smithsonian Contributions to History and Technology, Number 55, p. 49

On March 25, 1914, a test of the Farm-to-Table program was launched with twelve post offices. Albert S. Burleson, The Postmaster General described the results in his annual report for the year:

“Marvelous growth and development marks the recent history of the parcel post. Although in operation less than two years, this service has expanded from an experimental facility of limited advantages into a universal transportation agency ...

“The department ... believes that the parcel post, in time, will become an important factor in improving and cheapening the food supply of the great cities. Hence on March 25, 1914, 12 of the larger post offices were designated for special test of a farm-to-city service. Farmers were invited to register their names and designate the commodities they desired to sell. Lists of farmers and the articles each offered were then printed and distributed in the cities by the [postal] carrier force. The results exceeded expectations; shipments of country products at the 12 offices so materially increased that now 18 additional offices have been named for similar exploitation of the farm-to-city service. ...

“Farmers who quote prices lower than the city market prices ... have an opportunity for profitable and convenient marketing by parcel post. City consumers who get in touch with this class of farmer and impose reasonable requirements as to the grade of products furnished them obtain better quality at slightly lower prices"

United States. (1914). Post Office Department Annual Reports for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1914. Report of the Postmaster General. Washington, D.C: U.S. G.P.O., p. 10, 12, and 13.

Would this program based on the U.S. Postal Service be successful today?

Coming back to the modern farm-to-table movement, Thomas Keller, the James Beard Foundation award-winning, Michelin star-decorated chef and restaurateur behind Per Se and The French Laundry has a different perspective. “This whole idea of farm-to-table today is just absurd. Throughout history, food has been grown on a farm and brought to a table. So, is farm-to-table really new? That's just the absurdity of some of the definitions that we give our professional languages. Downright laughable. But I won't get on that. …

“One of the holy tenets of farm-to-table is supposed to be the fact that food goes directly from farm right to table, which is possible only in the event of restaurants literally located on farm grounds and offering extremely limited menus. In most cases, farm-to-table restaurants tout local suppliers, but there's seldom any consensus on the exact meaning of "local."

"Local, to me, is an irrelevant term," Keller said. "What's more important is quality."

https://www.myrecipes.com/extracrispy/thomas-keller-farm-to-table-absurd

https://www.mashed.com/358706/this-is-thomas-kellers-biggest-problem-with-farm-to-table/

Keller’s opinion is echoed by Chef William Dissen, owner of The Market Place restaurant in Asheville, North Carolina, Billy D's Fried Chicken in Asheboro, and Haymaker in Charlotte. An honors graduate from the Culinary Institute of America (this after earning a degree in French and English from West Virginia University), Dissen then trained and worked under Certified Master Chef Peter Trimmins and Chef Donald Barickman, and then earned a Master's Degree in Hospitality from the University of South Carolina.

“I think the phrase "farm-to-table" has become cliche and that everyone says they're farm-to-table. You see national pizza brands on commercials saying that they're farm-to-table. That to me is a little bit misleading. I really, to me, I think it's about a sense of place and community. We put seven figures or more a year from our restaurants back into the local community by sourcing the local fruit and vegetables, artisan ingredients. I think that trickle-down effect in the economy is real. You don't find that as much as you would in a big corporate world as you do in a smaller, independent farm-to-table style restaurant. And I think that sense of place is really burdened because of that.

“How can people cook and eat more sustainably in their everyday lives?”

The use of term “farm-to-table” emphasizes a direct relationship between a farm and a restaurant. The rarely articulated but fundamental underlying question is the farm practices? Does the farm follow organic practices, whether or not engaging in the certification process? No synthetic fertilizers, herbicides or pesticides? Non-GMO seeds? Biodynamic? Does the farm practice regenerative agriculture? Crucial questions almost never addressed on restaurant Websites or menus, as they should be. A bare assertion of “farm-to-table” is insufficient.

There are a number of produce services available today that provide subscription-based or one-time delivery from farms to your doorstep. Many of these services focus on sourcing from local farms to provide the freshest produce available. Look at Imperfect Foods, Farmbox Direct, The Chef’s Garden, The FruitGuys, and Melissa’s Produce. However, you have to ask these services the same questions as the restaurants; what are the supplier farm practices? Hint, the lower the price, the less likely the produce is organically and regeneratively grown. Or you can go to the local farmers market, or join a community garden and ask the questions directly.

In its most honest form, “farm-to-table” means the table is at the farm and chefs prepare and serve the food at the farm. Welcome to Borgo Santo Pietro, a 300-acre organically cultivated estate in Tuscany about 100 km south of Firenze (Florence) … hotel, Michelin-star restaurant, working farm, vineyards, olive trees, fruit and nut orchard, herb farm, spa and cooking school.

Each day Borgo Santo Pietro’s farmers collect milk from the 300 sheep herd that is transformed into artisan cheese and yogurt in the estate dairy; ricotta, ravaggiolo, primo sale, robiola, fiorito, pecorino and blue cheese, all served at the breakfast buffet and in the restaurants. Two apiaries provide honey from local bees free from chemicals and added sugar. Pigs roam through the forest to enjoy a diet of acorns that yield unique prosciutto. More than 200 vegetable species and 50 aromatic herbs are cultivated. The fruit orchard comprises apples, pears, peaches, cherries, plums and quinces; the nut orchard walnuts.

Borgo Santo Pietro’s own red and rosè wines are predominantly Sangiovese; Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Petit Verdot and Pinot Noir round out the reds. Whites include Trebbiano Toscano, Chardonnay and Viognier. Olive trees dot the estate and yield Borgo Santo Pietro’s specialty olive oil. Rosehip, rosemary, lavender, calendula, juniper, peppermint, melissa and hypericum are grown in a six-acre herb farm specifically for Borgo Santo Pietro’s regenerative skincare products … Seed to Skin. Beef comes from a local organic free-range farm.

You can walk to the free-range chicken coop and collect eggs for tomorrow’s breakfast.

The “farm” provides the ingredients that the chefs, gardeners, foragers, cheesemakers, bakers, the fermentation specialist, butcher, restaurant staff, and sommelier bring to the “table,” Borgo Santo Pietro’s Soil-to-Plate cuisine.

Ready to bring the Borgo Santo Pietro Tuscan experience home? Enroll in the Borgo Cooking School and get introduced to Mamma Olga, who shares her classic family recipes that have been passed down through generations of Tuscan cooks. An amazing experience with an amazing woman.

At one point Mamma Olga split a clove of garlic by passing the knife from the fat side of the clove to the thin side, cleaving the clove in half. She then proceeded to remove the sprout leaf from its center. Having never cleaned a clove this way, we asked Mamma Olga why she removed the removed the sprout leaf in the center. “It irritates the stomach and the intestines,” she responded, “it is not good to eat.” We travelled 6,000 miles to learn how to clean a clove of garlic! You can rest assured that we will ask all of our chef friends if they have ever been told this.

Borgo Santo Pietro is “farm-to-table” in the most exceptional experience, within a true sense of community.

https://borgosantopietro.com