We always have a few in the pantry; we grab and chop them for countless dishes … because that’s the way we learned; we mostly think about the other recipe ingredients … Onions, the steady, reliable food we rarely think about.

So what about onions? … Where do onions come from? Ok, yes, the garden, but … Onions are one of the oldest cultivated vegetables, originating in central Asia about 5,500 years ago. Organized onion cultivation started about 3,500 BC. Once civilizations started using onions, they became highly dependent on them. They are easy to grow in almost any kind of soil and weather, and they are easy to dry and store. The ancients knew onions prevented thirst, were a source of energy, and had medicinal properties. Onions were so revered they were included in religious rituals and celebrations. To the Egyptians onions were a symbol of eternity and endless life; they were part of burial ceremonies. Onions were also an important part of the Egyptian mumification process. One of the earliest cookbooks in recorded history, De re coquinaria (“The Art of Cooking”), published in the 5th century C.E., by Marus Gavius Apicius (simply known as Apicius), a wealthy Roman merchant and epicure, recommended minced, cooked onion as a sauce for stewed meat.

Scurvy was the scourge of world exploration sailing ships in the 1600s and 1700s … thousands of sailors died from the vitamin C deficiency. Sailors that ate raw onions did not get scurvy.

Food on sailing ships was definitely not haute cuisine, which evolved beginning about the same time as explorers began to venture in search of new lands. The basic onion was one of the foundational building blocks of French cuisine as it became a global force. Much of classic European gourmet food starts with a mirepoix, a simple blend of finely chopped onions, carrots, and celery slowly sauteed in olive oil. The flavor of onions is essential in almost every dish; tartness, bitterness, and sweetness.

Onions contain phytochemicals, compounds that plants produce to ward off harmful bacteria, viruses, and fungi; they are part of the plant’s immune system. Phytochemicals have antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties. Their effects are anti-obesity, antidiabetic, anticancer, protective to the cardiovascular, digestive, respiratory, reproductive, and neurological systems in the body, protective against liver disease, and support a healthy immune system. Additionally, onions relieve asthma, bronchitis, and coughing. Zhao, X., et al., “Recent advances in bioactive compounds, health functions, and safety concerns of onion (Allium cepa L.),” Front. Nutr. 8:669805 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.669805 Whew, you should immediately go get some onions.

Onions may be eaten raw or cooked; cooking them results in some loss in nutritional value. Thiosulfinates, one of the phytochemicals in onions, are sulfur-based compounds that give onions their distinctive pungent flavor. Wang, Y., et al., “Process flavors of Allium vegetables,” in Fruit and Vegetable Flavour (Elsevier Scientific, 2008). Thiosulfinates have antimicrobial, antifungal, and antibiotic properties. Bor, T., et al., “Antimicrobials from herbs, spices, and plants,” in Fruits, Vegetables, and Herbs (Elsevier Scientific, 2016). To be effective, the thiosulfinates need to be released from inside the onion cells. Crushing onions before cooking is one method to release the thiosulfinates. Another technique is to sauté chopped onions on extremely low heat for fifteen to twenty minutes, until they are translucent. The slow heating breaks down the onion cellular walls. If you are making a mirepoix, the garlic and other ingredients should be added to the sauté after the onions have cooked.

Onions also contain flavonoids, glutathione, selenium compounds, vitamin E, and vitamin C, which contribute to their antioxidant properties. Nicastro, H., et al., “Garlic and onions: Their cancer prevention properties,” Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 8(3):181-189 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207 Flavonoids reduce inflammation, regulate key cellular enzyme functions, reduce the risk of diabetes, and interfere with cancer development by preventing cellular mutation. Panche, A., et al., “Flavonoids: an overview,” J. Nutr. Sci. 5:e47 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2016.41; Al-Ishaq, R., et al., “Flavonoids and their anti-diabetic effects: cellular mechanisms and effects to improve blood sugar levels,” Biomolecules (9):430 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9090430 Flavonoids have also been shown to help reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s or other dementia. Shishtar, E., et al., “Long-term dietary flavonoid intake and risk of Alzheimer disease and related dementias in the Framingham Offspring Cohort,” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 112(2):343-353 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa079 Interestingly, baking onions is shown to increase flavonoids.

Like virtually all fruits and vegetables, onions can contain pesticide residue, heavy metals, microbial contaminants, and nitrate accumulation. As has been so often reiterated here, choose only organically grown onions, preferably from known local sources. Select onions that feel firm, have dry skins, and no bruises or discolored spots. Avoid onions that have white or black spots on their surface or inside layers, evidence of mold. Store onions in a cool, dry, and dark place. If the onion has sprouted, and shows a green shoot, it is still edible but will not last much longer.

Onions are part of the Allium plant genus, including plants like garlic, leeks, and chives.

The most common and widely available onions are red, yellow, Spanish, and white. Yellow onions are the all-purpose default choice. Spanish onions are a slightly sweeter type of yellow onion. White onions are milder and sweeter that their yellow cousins; great for pico de gallo. Red onions have a mild sweet taste that complements salads and tops burgers.

Other onions include red and white cipollini, and pearl onions. Pearl onions come in red, yellow and white, commonly found submerged in martinis. They are de rigueur for beef bourguignon.

Vidalia, Walla Walla, and Bermuda are all types of sweet onions. They tend to be somewhat larger and flatter shape than others; great for fried onion rings … yum. They are also sweeter, surprise, surprise; their higher sugar content makes them candidates for caramelizing.

Now for some confusion … green onions, scallions and chives. Green onions, sometimes called spring onions, look similar to scallions but have a small bulb at the base. They are not really a distinctive type onion, just white, yellow or red varieties harvested early in their growth. Scallions, are often called and confused with green onions, and vice versa. They have a long thin shape with white bottoms and dark green tops; the bottom white part is more pungent than the green tops. The dark green tops of scallions are often confused with chives, and often used interchangeably. Scallions have a stronger flavor than chives and can stand up to cooking much like their larger cousins.

Chives are actually members of the flowering plant lily family (Allium schoenoprasum) that produces edible leaves and flowers. They are close relatives to onions as well. Like onions, they are bulbous perennials, however, the below-ground bulbs are typically removed before packaging or use. Chives are herbs not vegetables; delicate and tender chopping them into small bits releases their oniony flavor. They can be sautéed, but overcooking weakens their flavor and texture. Chives are often used as a garnish … think of a baked potato with sour cream … or mixed into sour cream for dip … or topping deviled eggs.

Shallots, sometimes called French onions, are perhaps the most underrated variety of onion. Shallots were classified as a separate species until 2010, Allium ascalonicum, after which they were lumped together with common onions, Allium cepa. The most common shallot you find in stores is the Jersey shallot, which has a deeper, pink-copper color than the French red shallot, with its light purple flesh and slightly grayish skin tone. The name “shallot” is derived from the Old French eschalotte. Shallots are versatile, their pungent and garlicky flavor delicious raw, for example minced into vinaigrettes, and equally delicious when gently sautéed and added to sauces. Some describe sautéed shallots as candy because of their sweet taste.

Leeks are likewise under appreciated by many. They have a mildly sweet flavor; they are commonly used as part of a base of flavors for soups, stews, and other long-cooking dishes. Only the tender base white and light green parts of leeks are eaten. Smaller leeks tend to be more flavorful. They are rich in flavonoids, high in fiber, and a good source of vitamin K, which aids in blood clotting in wounds and helps reduce the risk of osteoporosis. A classic recipe is leek and potato soup in which both the leeks and the potatoes are pureed into a cream-based soup.

As you might expect, there are unique types of onions grown in various locales. For example, ramps, sometimes called Tennessee truffles (Allium tricoccum), are spring onions with red edible stems and long green leaves. Raw they taste like garlic; cooked they taste more like scallions.

Chinese onion is native to China but has been domesticated throughout Asia. Also known as Chinese Scallion, Japanese scallion, rakkyo and oriental onion, and has a mild taste and is often pickled and served alongside other dishes.

Where does garlic fit into the onion taxonomy? Garlic (Allium sativum) is a member of the onion family along with its cousins described above. Garlic does not appear in the wild as a species itself. It is believed that garlic is an evolved mutation of an extinct predecessor that has been used as a food source and as a medicinal plant for over 7,000 years. Ancient Egyptians fed garlic to the laborers building the great pyramids on the belief that garlic would increase their strength and stamina. Hippocrates, the Greek Father of Medicine, advocated garlic for pulmonary and abdominal issues as a cleansing agent. In his book Historia Naturatis, the famous Roman naturalist Pliney the Elder recommended garlic for gastrointestinal disorders, seizures, and skeletal diseases. Charaka-Samhita, a medical text in India, recommended garlic to treat heart disease and arthritis. In ancient China and Japan, garlic was prescribed to help digestion, cure diarrhea, and alleviate depression.

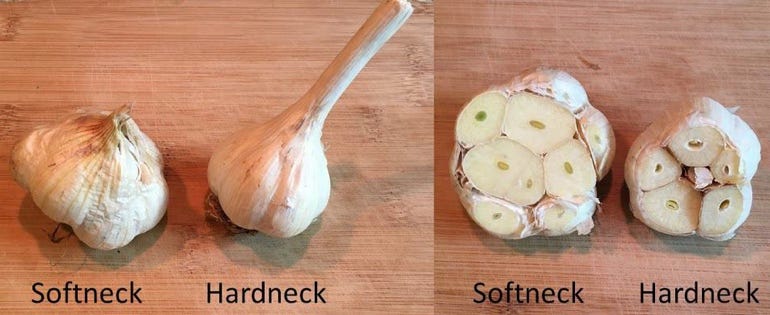

There are two varieties of garlic, hardneck and softneck. The term “neck” refers to the stalk that grows from the garlic bulb. Softneck stalks are bunched leaves; hardneck has a rigid stem. You find softnecks predominantly in grocery stores. They have a mild flavor and store well. Hardnecks have more complex flavors, but have a much shorter shelf life.

We learned from Mama Olga, Tuscan grandmother, to remove the germ of a garlic clove, the very center of the clove. The germ sprouts a little green stem when it starts to germinate. It has a strong bitter flavor and can irritate the intestines. On the other hand, Marcella Hazan, who many consider the Julia Child of Italian cooking, never removed the germ. Whether you do so or not is up to you; experiment for your taste.

We cannot talk about onions without talking about tears, yours. Onions come standard equipment with a defense mechanism to protect themselves from hungry animals as they grow. Onions effuse enzymes and sulfenic acid when their skin is broken to produce propanethial S-oxide, a lachrymatory agent … a gas that generates tears when it reaches your eyes. Ready for this, propanethial S-oxide turns into sulfuric acid when it comes into contact with the water layer over your eyes. Akin to the onion, you also come standard with a defensive mechanism, your eye generates tears to flush away the sulfuric acid.

Yellow, red, and white onions are the worst offenders because they contain a lot of sulfur-containing compounds. Sweeter and smaller onions, scallions, for example, have less sulfur compounds, are less pungent, and usually cause fewer tears. Of course, sometimes you are lucky and get onions that do not cause tears; other times your eyes are more like Niagara Falls. The root ends of onions have the highest concentrations of sulfuric compounds, so try to avoid cutting there. Also, the sharper the knife, the less the damage and the less propanethial S-oxide released.

Want to grow your own onions? What do you need to know?

First, you need a little geography. The amount of available sunlight, that is, the length of the growing day, has a major influence on onion quality and yield. This is the time it takes to form a bulb. Savonen, C., “Onion bulb formation is strongly linked with day length,” Oregon State University Extension Service | Gardening (2006). Sunlight hours signal to the plant to reduce the energy devoted to developing green tops and devote it to growing the bulb below ground. Bulb onions (Allium cepa) are separated into three types: short-day, medium/intermediate-day, and long-day. Day length corresponds to latitude. Picture the United States divided by latitude into three horizontal zones. Correspondingly, short-day onions grow best in southern latitudes, below the 36th parallel north; medium/intermediate-day onions grow best in mid latitudes; long-day onions grow best in northern latitudes, above the 36th parallel north. Seed catalogs give us information about which onions to grow where.

“Short-day onions, such as Vidalia onions from Georgia, require the shortest day length to form bulbs—typically under 12 hours. They are traditionally grown in southern states during the late winter to be harvested the following winter or early spring (Shock, 2013). For example, south Texas grows short-day onions such as the famous yellow 1015 “Million Dollar Baby” onions (Bond, 2013). Medium-day onions, or intermediate-day onions, require 12 to 14 hours of daylight for bulb formation and can be grown in the aforementioned “central latitudes” of the United States. A few examples of intermediate onions are the white Superstar onions, Utah Sweet Yellow Spanish onions, and Sweet Red onions. These are planted in the fall and harvested in late spring/early summer. Long-day onions require 14 or more hours of daylight to initiate bulb formation and can be grown in the northernmost states like Oregon and Washington. The most popular long-day onion variety in Malheur County and Southwest Idaho is ‘Vaquero’.” “Types of Onions and Varieties,” Oregon State University College of Agricultural Sciences, Malheur Experiment Station (2022). https://agsci.oregonstate.edu/mes/sustainable-onion-production/types-onions-and-varieties

As with wine grapes, the taste of onions is directly influenced by the soil in which they are grown, terroir. Plant onions in full sun in loamy, loose, and well-drained soil with a neutral pH. Compacted and heavy clay soils can affect how onion bulbs develop. The more water they receive, the sweeter the onion. Onions get along great with members of the Brassicafamily, broccoli, cabbage, kale, and Brussels sprouts, and tomatoes, lettuce, peppers, and strawberries. They do not get along with other onion cultivars and garlic. Beans, peas, sage, and asparagus should also not be in the neighborhood. Onion varieties should be rotated in annual plantings.

How about some special recipes around onions. Here’s a camping recipe from a 1936 edition of the Boy Scout Handbook … campfire eggs. Cut a large sweet onion in half and scoop out a few of the center rings. Wrap each half in aluminum foil. Crack one or two eggs into the scooped-out rings, and place into campfire coals. Roast until the egg is done to your satisfaction.

Of course, you can cut onion rings, fairly thick, crack an egg into the center, and fry the combination in a skillet. A little cheese on top, chives, bacon bits … yum, breakfast or anytime.

A basic omelet taken to a new level of creaminess … the French Boursin Omelet

2 tablespoons plus 1 teaspoon unsalted butter, divided

1 cup finely chopped shallots

2 tablespoons water

1/4 teaspoon French sea salt, divided, plus more to taste

2 large eggs

1 teaspoon heavy cream

1-3 tablespoons spreadable cheese, such as Boursin, at room temperature

1 teaspoon finely chopped fresh chives

Want to spice it up, add crab meat, shrimp, jambon, or cook some bacon and add crumbles.

Heat 1-2 tablespoons of butter in an 8 to 8 1/2-inch nonstick skillet or omelet pan over medium-high heat. Add shallots, and spread in an even layer. Sauté, undisturbed, until shallots begin to brown, about 4 minutes. Add a tablespoon of water and 1/8 teaspoon salt; sauté, stirring constantly, until shallots are softened and golden brown, 8 to 10 minutes. Transfer shallots to a bowl. Wipe skillet clean.

Gently whisk together eggs, cream, and remaining 1/8 teaspoon salt in a medium bowl until well combined. Try not to introduce too much air. You do not want the egg mixture too frothy.

Reheat the same skillet or omelet pan over medium-high heat. Add 1 tablespoon butter (it should melt almost immediately) and swirl to evenly coat the bottom of the skillet or omelet pan. Just as butter stops foaming but before it begins to brown, add egg mixture all at once. Cook, stirring constantly with a heatproof rubber spatula, until mixture thickens slightly into very soft scrambled eggs with thin ribbons of set curd running throughout, 10 to 20 seconds. Gently shake skillet to form an even sheet of eggs on bottom of skillet.

Reduce heat to low. Crumble cheese in a line across the center of the eggs (how cheesy do you want your omelet?). Sprinkle caramelized onions over the cheese (use as many onions as you desire). If you are going to spice up your omelet, now is the time to add the additional ingredients.

Cook omelet, undisturbed, until filling heats and cheese melts, about 1 minute (the more ingredients you add, the longer it will take). Using spatula and starting on one side, gently fold omelet over, just covering filling. Switch to the other side and roll up the entire omelet.

Turn off the heat, and let stand 10 seconds. Transfer to a warm plate, and rub hot omelet with remaining 1 teaspoon butter. Sprinkle with chives, and add salt to taste. Serve immediately.

Pairings: Crusty French baguette, a crisp salad, and a glass of French Chablis.

As Ellie said very educational.

Your writings about various edibles and haute cuisine... are always interesting, amusing, fascinating and educational ... and addressed to our health! Thank you! Write more! Write often